“…man now realises that he is an accident, that he is a completely futile being, that he has to play out the game without reason. I think that even when Velasquez was painting, they were still, whatever their attitude to life, slightly conditioned by certain types of religious possibilities, which man now, you could say, has had cancelled out for him. Man now can only attempt to beguile himself, for a time, by prolonging his life – by buying a kind immortality through the doctors. You see, painting has become, all art has become a game by which man distracts himself. And you may say it has always been like that, but now it’s entirely a game. What is fascinating is that it’s going to become much more difficult for the artist, because he must really deepen the game to be any good at all, so that he can make life a bit more exciting.“”

-Francis Bacon 1

These words, spoken by Bacon in an interview in 1963, midway through his painting career, harken upon an illustration set down by Albert Camus in his “The Myth of Sisyphus” of the vocation of the artist living in an absurd world. Yet of great interest in the life and works of this man, one of the most controversial painters of the 20th. Century, is the meaning of such a tenet of absurdity in his medium and, like Camus, times. Indeed, while the absurdist logic had tended to dwindle passed the 1960’s, being drowned out by newer and more complex conflicts of war, politics, and general means of living (e.g. pop culture, technology, etc.), Bacon had tended to remain true to a fundamental understanding of life and death that few have managed to do. In understanding that, his, “understanding”, it is crucial to look upon his works and the manner with which he created. We must ask the “who?” and the “how?”, as Bacon had always strongly absolved the “what?” and the “why?”. For surely, he had once said, with regards to his painting, “If I didn’t have to live, I’d never let any of it out.”2

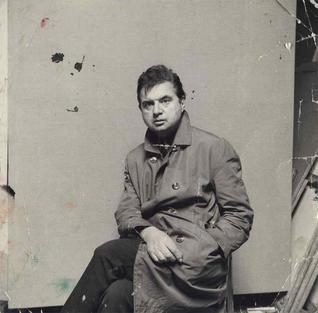

When asking who Bacon was and how he created, we will find that placing him into a contextual setting is a highly problematic endeavour. He was certainly one of the most unique painters of this century and was, in many ways, truly ahead of his time. His works have been explained both in terms of Surrealism and Cubism, but Bacon, himself, finds his work to fall greatly away from any of these genres. He was self-educated, took no formal art lessons, and his influences from Picasso, Velasquez, Muybridge and Eisenstein do little to produce a good definition of his art. This is not to say, however, that we can not fix a meaning to him and his chronology. For it would be highly unlikely that a Bacon could have been produced before the 20th. Century, and there could have been only a small span of years after he came about that a man such as himself could have been produced. So how then could we start to understand a painter like Bacon? In order to do so, we must look at the greater of the unique natures of this man and his times. We must look at the man.

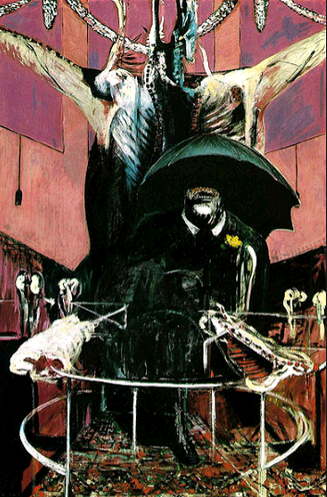

Who Bacon was and how his paintings came about becomes quite apparent in his response to a question posed in an interview with a good friend of his, David Sylvester. Sylvester related how a critic had once said that Bacon could be a fine painter if, instead of using horrific subject matter, he would paint beautiful things such as a rose. Bacon replied how, if we thought about it, even a rose will begin to wither after two days; its head falling from its stem. He went on to say that, “the more violently, more strongly, you feel about life, the more strongly you must be aware of death.”3

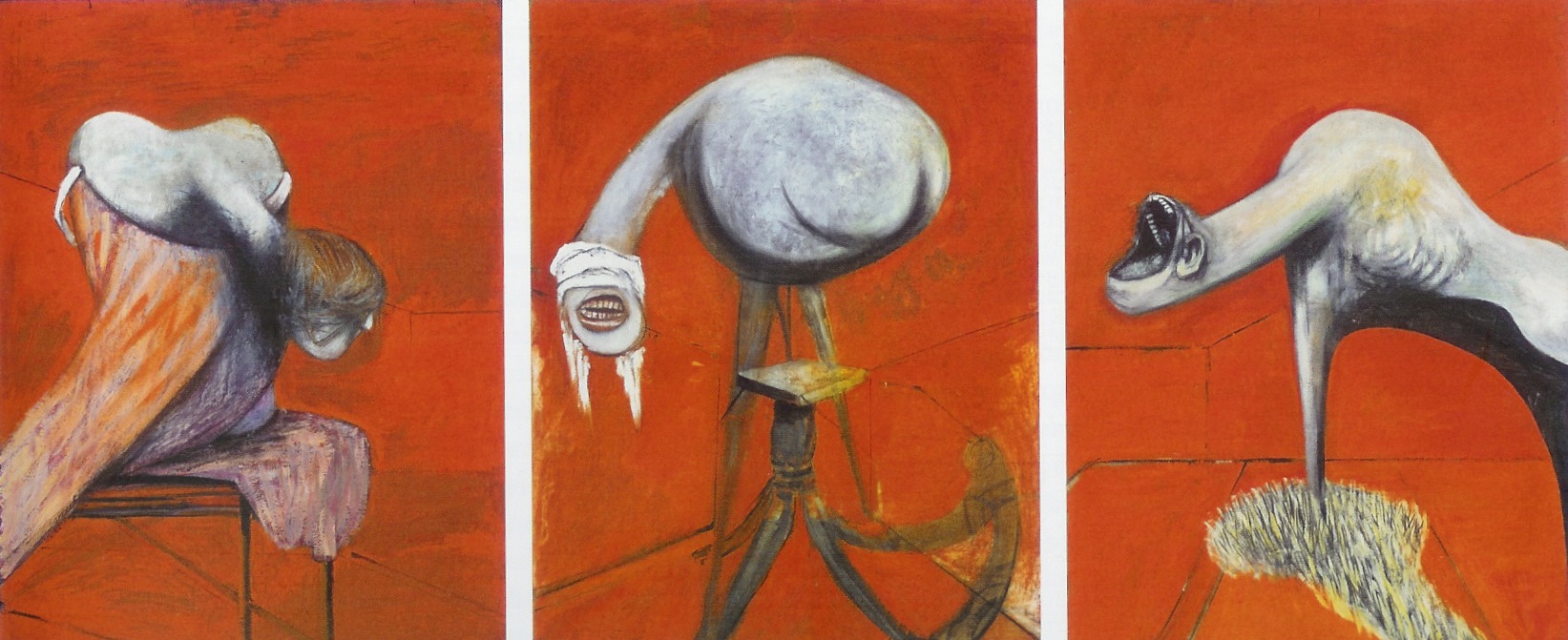

It is with violence that Bacon regards his work. But it is not a violence of destruction, instead, it is a violence of marriage – such as between life and death. Bacon, himself, is optimistic towards life, but he says that his optimism comes from “nothing”.4 From this standpoint and his quote that opened this discussion, we can come to acknowledge a major artery of Bacon which is characteristic of the existentialist movement that began towards the end of the 19th. Century and continued on to the first half of the 20th. Century, where man “had cancelled out for him” any possibilities other than the here and now. It was this understanding that gave him the context for his life; the optimism was reached through a more individual, humanistic sense, the likes of which still can not be properly explained by psychology or philosophy.

What we do know, however, of Bacon’s individual, humanistic sense is that he enjoyed partaking in the delights of the flesh. He enjoyed drinking a great deal, gambling, friends, and the loves of another human being (which was, by the way, homosexual if anyone would like to read any more into the fact).

Bacon embraced the humanistic side of life, and he viewed it as being quite human, but also not denying a certain animalism. For “we are animals, aren’t we?” he says.5 And it is with this animalism that Bacon creates, working in an unmeditated fashion that resides in the moment. In painting, he says how he depends more on chance and instinct rather than intellect. When asked why he regards chance as more important than intellect, he replied, “I make images that intellect would never make.”6

This is not to say, however, that Bacon’s work is devoid of a higher thought, rather it is born through an action, a movement of life that has been developed and transfigured by human thought through an unconscious, instinctual persona – a freedom of sorts, both raw and full. The fact that Bacon does not consider his work horrific reveals the value of this freedom and of its honesty. When pressed about the apparent violence of his work, he says, “What could I make to compete [with] what goes on every single day… if you know what goes on in this world.”7

1 Russel, John. Francis Bacon. (London: Methuen London, 1964). P. 1

2 Russel.

3 Francis Bacon and the Brutality of Fact (video). A Michael Blackwood Film. Dist.by Tate Gallery Publication. (1984).

4 Francis Bacon and the Brutality of Fact.

5 Francis Bacon (video). Produced and Directed by David Hinton. R.M. Associates. (1985).

6 Francis Bacon (video).

7 Francis Bacon (video).